Written by Travis Brege with Dr. Nabil Ebraheim

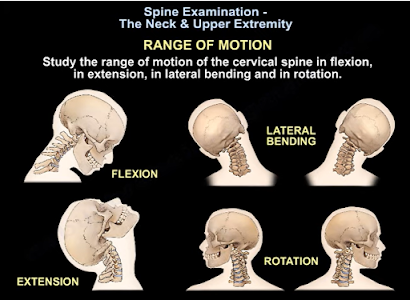

The steps of any orthopedic examination will follow the pattern of inspection, palpation, range of motion, and tests of strength for the key groups of muscles applying all the appropriate provocative tests and neurovascular examinations.

First, in the inspection of the spine, look for any visible deformities in the coronal (frontal) and sagittal (longitudinal) planes. In the coronal plane, check for scoliosis and pelvic obliquity1. In the sagittal plane, check for normal cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, and lumbar lordosis2. While assessing the symmetry of the whole body, make sure to assess the skin for lesions, hairy patches, dimples, surgical scars, muscular atrophy, and anything else that may be abnormal.

Next, you want to palpate the iliac crests, posterior superior iliac spines, spinous processes, sacrum, trochanters, and ischial tuberosities. Palpate the soft tissue as well, assessing trigger points such as the gluteus muscles, piriformis, and sciatic nerve.

Assess the patient’s movement first with their gait as certain gaits may indicate various pathologies (ie. antalgic, Trendelenburg, steppage, and staggering gaits)3. Then, check the movements of the lower spine to identify if any causes pain; for example, extension of the spine creates pain in lumbar stenosis4, while spinal flexion can create pain when a disk pathology is present5.

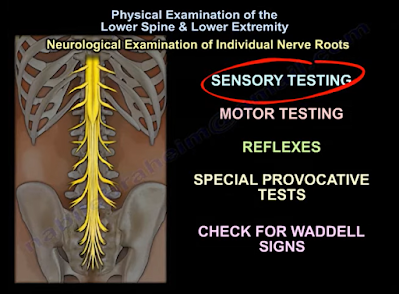

Now, we can assess the individual nerve roots from L2-S1 using sensory and motor testing, reflex tests, specific provocative tests, and check for Waddell Signs.

In sensory testing, the areas that can be assessed include pain, light touch, temperature, and proprioception (awareness of the position of one’s body). Sensory testing can indicate a spinal root pathology in the presence of a dermatomal pattern of dysfunction, or it can suggest a neuropathy in the presence of a glove-and-stocking distribution of sensory dysfunction6. The specific pattern of sensory distribution in the lower extremities can be normal, impaired, or completely absent in some cases.

In motor testing, the action of hip flexion comes largely from the iliopsoas muscle, which is innervated by the L1, L2, and L3 lumbar nerve roots. Hip abduction is completed through the L2, L3, and L4 lumbar nerve roots. Knee extension is innervated by the L2, L3, and L4 lumbar nerve roots. Dorsiflexion is largely performed via the tibialis anterior muscle which is innervated by the L4 lumbar nerve root. Extension of the hallux is mainly innervated by the L5 lumbar nerve root. Ankle plantarflexion is performed using the gastro-soleus complex whose main innervation is from the S1 sacral nerve root7.

For reflexes, only two exist in the lower extremity that are utilized in physical examination. The Patellar Reflex which is innervated by the L4 lumbar nerve root, and the Achilles Tendon Reflex which is innervated by the S1 sacral nerve root7.

Provocative and special tests can be used to help differentiate between musculoskeletal pathology and spinal pathology. These include the Straight Leg Raising Test for L5-S1 nerve root irritation8 and the Femoral Stretch Test for L3-L4 nerve root irritation9. Upper motor neuron lesions can be identified or ruled out utilizing the Clonus Test10 and the Babinski Test11. The Bulbocavernosus Reflex can be utilized to detect spinal shock12. The Faber (Flexion, ABduction, External Rotation) Test is a good test for assessing the sacroiliac joint, but it is NOT confirmatory13,14. Sacroiliac joint test is usually confirmed by the injection of an anesthetic with a positive response for reduction of pain15.

Waddell’s Signs are controversial, however, assessing for these signs can be included as a part of a thorough physical examination for a patient that presents with lower back pain. Waddell’s Signs include: (1) superficial tenderness, (2) non-anatomical tenderness (tenderness that exists over a wide area that goes beyond a single anatomical boundary), (3) axial loading pain on the patient’s head that elicits low back pain, (4) acetabular rotation causing low back pain, (5) distracted straight leg discrepancy, (6) regional sensory disturbances, (7) regional muscle weakness that can’t be explained on an anatomical basis, and (8) overreaction to a pain stimulus that isn’t reproduced when the same provocation is applied at a later time16.

References

1. Janicki JA, Alman B. Scoliosis: Review of diagnosis and treatment. Paediatr Child Health. 2007 Nov;12(9):771-6. doi: 10.1093/pch/12.9.771. PMID: 19030463; PMCID: PMC2532872.

2. Scheer JK, Tang JA, Smith JS, Acosta FL Jr, Protopsaltis TS, Blondel B, Bess S, Shaffrey CI, Deviren V, Lafage V, Schwab F, Ames CP; International Spine Study Group. Cervical spine alignment, sagittal deformity, and clinical implications: a review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013 Aug;19(2):141-59. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.SPINE12838. Epub 2013 Jun 14. PMID: 23768023.

3. Lim MR, Huang RC, Wu A, Girardi FP, Cammisa FP Jr. Evaluation of the elderly patient with an abnormal gait. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007 Feb;15(2):107-17. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200702000-00005. PMID: 17277257.

4. Katz JN, Harris MB. Clinical practice. Lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2008 Feb 21;358(8):818-25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0708097. PMID: 18287604.

5. Kuai S, Liu W, Ji R, Zhou W. The Effect of Lumbar Disc Herniation on Spine Loading Characteristics during Trunk Flexion and Two Types of Picking Up Activities. J Healthc Eng. 2017;2017:6294503. doi: 10.1155/2017/6294503. Epub 2017 Jun 11. PMID: 29065628; PMCID: PMC5485332.

6. Scott K, Kothari MJ. Evaluating the patient with peripheral nervous system complaints. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2005 Feb;105(2):71-83. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2005.105.2.71. PMID: 15784929.

7. Basit H. Anatomy, Back, Spinal Nerve-Muscle Innervation [Internet]. StatPearls [Internet]. U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2021 [cited 2021Oct25]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538322/?report=classic

8. Capra F, Vanti C, Donati R, Tombetti S, O'Reilly C, Pillastrini P. Validity of the straight-leg raise test for patients with sciatic pain with or without lumbar pain using magnetic resonance imaging results as a reference standard. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011 May;34(4):231-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2011.04.010. Epub 2011 May 5. PMID: 21621724.

9. Suri P, Rainville J, Katz JN, Jouve C, Hartigan C, Limke J, Pena E, Li L, Swaim B, Hunter DJ. The accuracy of the physical examination for the diagnosis of midlumbar and low lumbar nerve root impingement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011 Jan 1;36(1):63-73. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c953cc. PMID: 20543768; PMCID: PMC2978791.

10. Zimmerman B, Hubbard JB. Clonus. 2021 Aug 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–. PMID: 30521283.

11. van Gijn J. The Babinski reflex. Postgrad Med J. 1995 Nov;71(841):645-8. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.71.841.645. PMID: 7494766; PMCID: PMC2398330.

12. Ko HY. Revisit Spinal Shock: Pattern of Reflex Evolution during Spinal Shock. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2018 Oct;14(2):47-54. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2018.14.2.47. Epub 2018 Oct 31. PMID: 30402418; PMCID: PMC6218357.

13. Cattley P, Winyard J, Trevaskis J, Eaton S. Validity and reliability of clinical tests for the sacroiliac joint. A review of literature. Australas Chiropr Osteopathy. 2002 Nov;10(2):73-80. PMID: 17987177; PMCID: PMC2051080.

14. Nejati P, Sartaj E, Imani F, Moeineddin R, Nejati L, Safavi M. Accuracy of the Diagnostic Tests of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction. J Chiropr Med. 2020 Mar;19(1):28-37. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2019.12.002. Epub 2020 Sep 12. PMID: 33192189; PMCID: PMC7646135.

15. Jung MW, Schellhas K, Johnson B. Use of Diagnostic Injections to Evaluate Sacroiliac Joint Pain. Int J Spine Surg. 2020 Feb 10;14(Suppl 1):30-34. doi: 10.14444/6081. PMID: 32123655; PMCID: PMC7041665.