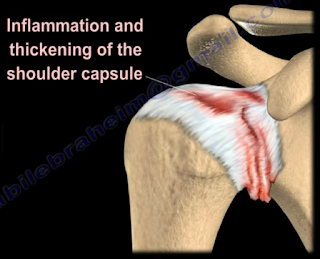

Adhesive Capsulitis, or frozen shoulder, is a painful progressive

loss of shoulder motion. It affects both active and passive movement of the

shoulder joint. The shoulder will be stiff and painful and occurs due to

inflammation, fibrosis, scarring, and contraction of the capsule. A normal

shoulder joint capsule is elastic and allows great range of motion.

Inflammation and thickening of the shoulder capsule and may lead to adhesive

capsulitis. Frozen shoulder may occur without any specific cause, however it

may be triggered by a mild trauma to the shoulder.

This condition develops slowly and goes through three

phases:

- Pain and freezing

- Stiffness or frozen

- Resolution

During the pain and freezing phase, the pain is worse at

night and increases with any movement. This phase will last several months.

During the second phase, range of motion is limited as pain is diminishing.

This may last up to one year. The resolution phase may begin overtime and may

last up to three years.

Conditions associated with frozen shoulder include:

- Diabetes

- Thyroid problems

- Auto immune disease

- Stroke

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Trauma or post-surgery

A patient with frozen shoulder will have loss of both active

(movement without assistance) and passive (movement with assistance) motion.

External rotation of the shoulder is very limited and the condition is

self-limiting and may resolve on its own. X-rays are needed to rule out

degenerative arthritis. An MRI or

arthrogram will show small fluid in joint cavity. Rotator cuff may be normal

and synovitis and narrowing of the rotator cuff interval is usually seen.

Treatment consists of anti-inflammatory medications,

physical therapy, injections, and manipulation under anesthesia. Surgery will

be done in the form of a release of the capsule when nonoperative methods fail.

The physician should always check the patient for diabetes.